Chilean Winter

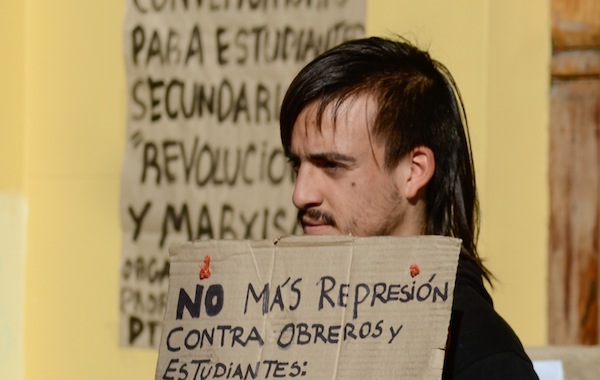

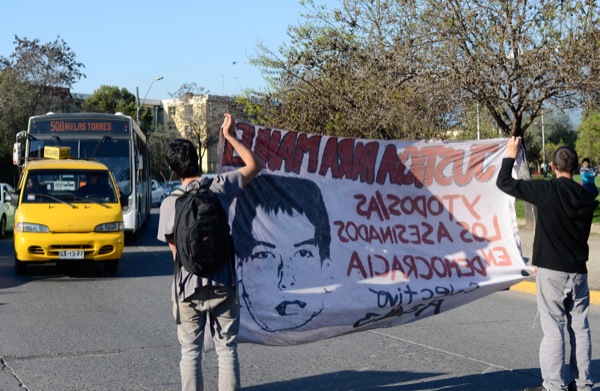

Tiny hands putting protests in larger perspectives

By Suzy Strutner

I went to Chile with a purpose: to understand why the students there protest their education system. Before leaving, I spent months interviewing professors in offices and sitting at long tables with government researchers and making calls on Skype from my bedroom in Westwood to high school administrators in Santiago.

But none of those official sources gave me answers that put the protests in perspective as much as some questions did – questions from a class of Chilean first-graders.

Even though it was daytime, the rain made Santiago a singular shade of gray. Jenna and I walked quickly past abandoned car dealerships and Internet cafes with barred windows. Icy wind whistled through empty alleys. We had heard there was a school around there, but I was ready to quit looking and bolt back to the Metro stop.

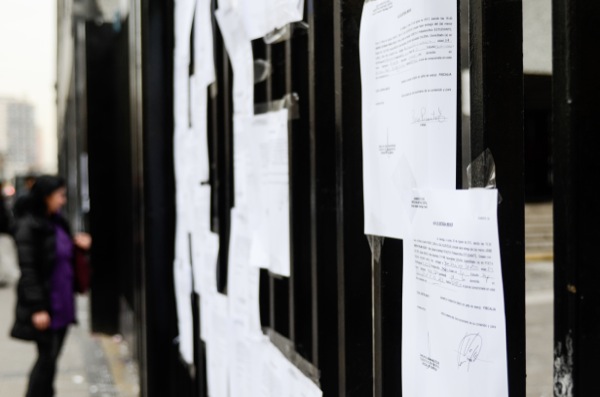

Then we found it, a little elementary school behind an iron gate. A teacher named Linda welcomed us inside. As she led us through the playground full of puddles, she told us how the students we saw weren’t supposed to be at this school. Chile’s earthquake in 2010 destroyed their regular school grounds. Their poor district lacks the income from taxes to rebuild, so the students come here for class after the campus’ other students leave for the day.

I had forgotten how tiny those elementary school chairs are. We sat in the back of the classroom, watching the little girl with curly pigtails pull a pencil out of her Disney princess backpack. A boy in a fluffy parka fidgeted and scratched his nose, squinting to make out the numbers on the board. Linda walked her students through a word problem about Miguel taking apples from a basket. Simple subtraction. In California, I learned subtraction at the same age, in the same way.

When I was in first grade, I wanted to write stories in magazines someday. I still do. And I probably will, probably because I went to a good college.

But this wasn’t my first-grade classroom.

I wriggled out of my chair and took a spot at the front of the class. As a reward for counting Miguel’s apples, the kids got to ask me questions about California.

The boy in the parka raised his hand.

“Have you seen a real skateboard before?”

Three more hands.

“Does your car have suicide doors?”

Seven hands.

“Are you … a millionaire?”

Their little palms rubbed together as I answered in imperfect Spanish that yes, I owned a skateboard. They smiled awestruck smiles. They flailed their arms in the air and yelped at their teacher, desperate for more information. I didn’t know what to say when we left, so I told them I’d see them in California.

But I don’t know whether they will ever make it to California, or even to the skate parks in Santiago’s upscale neighborhoods.

As Jenna and I walked back to the Metro stop, I was still giggling. But inside, I was hurting.

I could spend months interviewing professors and sitting at long tables and making calls on Skype, looking for answers about the future of Chile’s education system and not finding many.

I met dozens of people in Chile who told me the first nearly two years of protests for more accessible higher education have not resulted in many concrete changes in the system. Even if laws are introduced that make way for kids from non-elite schools to attend college, it would take years for the effects to trickle down to Linda’s students. It is possible that the kids I met that rainy afternoon in August may never get answers to their questions about life beyond Santiago’s poorest neighborhoods.

Their lack of answers is a bigger problem than mine.

Email Strutner at [email protected].